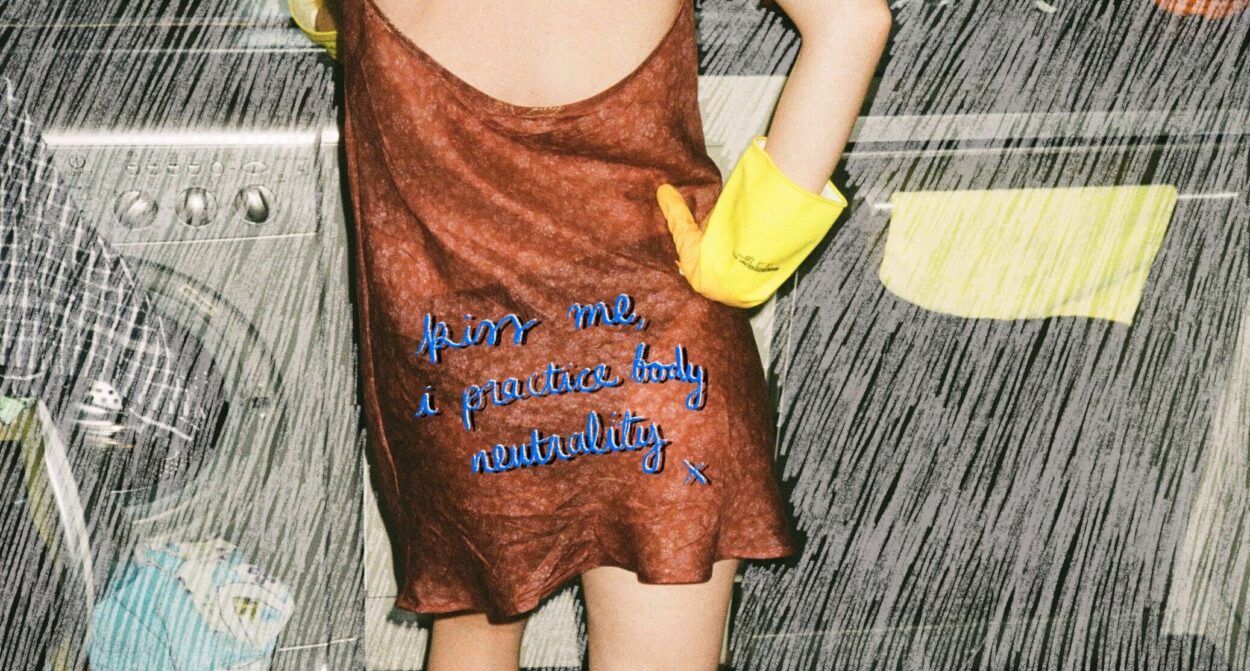

By empowering women to choose their own ideals of beauty, women, especially those in less privileged bodies, are free to exist in any way they please. To take it a step further, one might even reject the need to feel beautiful at all.

Beauty and Power – how far can the body positivity movement take us?

The body positivity movement’s philosophy of radical self-love is one of the most significant influences on our generations’ self-image. It’s an inclusive and extraordinary development, working towards the dismantling of conventional beauty standards, based on whiteness, Eurocentric characteristics, thinness and able-bodiedness.

However, how far can everyone and every body be treated with the same respect and same encouragement towards self-love, if beauty itself is still considered an achievement? Especially for women? Has this need for perfection become so internalised that the same beauty standards persevere, but just under a different name?

Humans have always endeavoured to be ‘perfect’, to improve oneself. This Age of Perfectionism – a term coined by Will Storr – finds its roots in Ancient Greece, a culture equally obsessed with celebrity, freedom, democracy, and the pursuit of the perfect human-self. You just need to read a few pages of Homer’s Iliad to see how honour, glory and beauty, above all else, were the true markings of a hero like Achilles or Hector. However, it’s not just an obsession with perfection that is deeply human, but also an obsession with authenticity. Our need to be (or at least be seen to be) ‘natural’, verges on fetishization and is visible today in our insatiable need to document our entire lives online. As Will Storr has commented, the internet has become a global online group in which the currency is the self, and its gold standard is personal openness and authenticity. It’s in the realm of social media, where perfection and authenticity are paradoxically intertwined that the body positivity and self-love movements find their home.

This movement rejects perfection, and embraces ‘realness’ in all its forms, especially the forms which have been hidden from mainstream view. Women, the section of the population who have been most afflicted by strict beauty standards, are the ones who stand to benefit most. Women of different sizes, colours, ethnicities, facial characteristics, and with varying disabilities have taken centre stage to represent the millions of others who look the same.

The celebration of difference and diversity has had real impact, with fashion brands such as H&M and ASOS embracing diversity in both their sizing range and with the diverse set of models they use online. Even established celebrities such as Kim Kardashian has built her SKIMS underwear campaign on the notion that her clothing fits a broad variety of bodies.

Over the past few years, we’ve seen a boost of bigger bodies commanding the front pages of some of the world’s most prestigious fashion magazines and campaigns. From Ashley Graham’s 2016 Sports Illustrated cover to the 2018 cover of British Vogue, which celebrated women of different ethnicities and sizes. Popular TV shows like Euphoria have written in plus-sized characters as sexy, empowered women. Whilst other shows like Netflix’s Never Have I Ever and the Sharma Family in Bridgerton Season Two, have both been described as a watershed for South Asian representation in the media, with their characters playing central love-interests with true complexities. Body positivity and the diversification of ‘beauty’ has all had a hugely positive impact on representation, and women’s self-image.

However, the one glaring fact of this is that all these women are conventionally beautiful; their facial features being typical of contemporary western conventions of beauty – small noses, big eyes, full lips and slim faces. The media we consume tells us time and again that if an individual doesn’t adhere to one of the traditional standards of beauty such as: whiteness, thinness, able-bodiedness and youth, then they must excel elsewhere. For example, some of the most well-known names in the fat acceptance movement such as Ashley Graham and Paloma Elesser still have conventionally beautiful faces and are big ‘in the right places’, sporting curves and voluptuous silhouettes. However, Lizzo is one of the few public figures to ‘go against the grain’; she’s black, fat and takes pride in natural traits often deemed as imperfections, such as cellulite. However, to be afforded this acceptance, she must be an astoundingly talented singer, songwriter, flute player, dancer, activist and trend-setter. Society has only allowed Lizzo to display herself fully, because she excels in other areas of her life. With a full team of stylists, make-up artists and gym trainers, Lizzo is not allowed to simply exist in the same way white, thin and ‘eurocentric’ women are.

A simple solution to this has been the move towards female empowerment in general, arguing that women should define what beauty standards they want to adhere to. In theory, it’s perfect. By empowering women to choose their own ideals of beauty, women, especially those in less privileged bodies, are free to exist in any way they please. To take it a step further, one might even reject the need to feel beautiful at all.

This is ‘body neutrality’; the idea that your body is there to be used and lived in, rather than to be loved and viewed as an aesthetically pleasing thing.

However, in practice, the liberal notion that choice and personal responsibility, as well as beauty and emotion, exist in a vacuum outside of society, is misled. The discourse surrounding female body hair is the perfect example of how often choice is intrinsically linked to cultural standards of attractiveness. Many companies that promote hair removal for women have followed the trend towards this freedom of choice; advertising themselves as bulwarks of female empowerment, as they bravely show a woman shaving a hairy leg, taglines read: ‘Be the best version of yourself with razors made just for you’. Apparently, women can now choose to shave, or they can choose not to. However, women have been told for decades that hairlessness is beautiful. The decision to shave has become rooted in insecurity and the desire to be ‘sexy’. This is demonstrated by the rise in permanent removal solutions like laser hair removal, which is growing in popularity 20 times faster than any other form of hair removal. As body hair can naturally be thicker on women of colour, it is again women in less privileged bodies that are disproportionately affected. So, choice is limited when these choices are still informed by strict standards of beauty.

By deconstructing the harmful narratives which suggest that beauty is the primary achievement a woman can hope to accomplish, we can stress how a woman can be worthy without being held to ever changing standards of beauty. This can only be done with the help of people who live in smaller, privileged bodies, to uplift the platforms and voices of those who are otherwise disregarded due to how they look. Indeed, it is both the body positivity movement and the body neutrality movement which will further the goals of female self-love and acceptance.

Graphic by the lovely Lucia Villegas.

Leave a Comment