CW: Rape and sexual assault.

A powerful and important article by Clara, on public consciousness, reporting rape, and what we can all do to challenge rape culture and support survivors…

CW: Rape and sexual assault.

A powerful and important article by Clara, on public consciousness, reporting rape, and what we can all do to challenge rape culture and support survivors…

I am a person who likes to read the news. I’m also a survivor of rape. It is the most awful thing that has ever happened to me. I’ve confronted a lot of things about my rape, and I’d say I’ve got to a stage where the pain comes and goes, but if there’s one thing that reliably puts it at the top of my mind again, it’s media coverage of sexual violence. My experience doesn’t make me an expert, but I’d like to share some thoughts about the cases that stay in the public consciousness, reporting rape, and what we can all do about the issue.

First of all, I think there’s something incredibly strange about the fact that the perpetrators dominating the news tend to be famous. Accused perpetrators have come from entertainment, sports, and even the government. We have conversations about the impact of fame and wealth, about the protection that comes with both, about reputation. We talk about power, in that we talk about men who get it, then misuse it. We talk about “open secrets” in high-powered or high-attention industries; we hear about reports that fell on deaf ears. All of this perpetuates myths. All of it makes me feel that there was no public interest in pursuing my report, because my rapist is a “normal guy”. Allegations against celebrities take the problem away from us, and out of our hands, into a “different world”: into much more public spaces. And perhaps this is why so much vitriol is directed at survivors with celebrity perpetrators; distance and online anonymity embolden people who seek to harm others. But that vitriol bleeds into real life, especially when those survivors choose to engage with the institutions involved in justice…

“Under questioning from Mr Spacey’s lawyer, Patrick Gibbs KC, the complainants had all denied either seeking financial gain, attempting to further their career or giving false accounts to the jury” – BBC news, 26/07/2023.

We see this a lot, right? There’s this idea that people who allege sexual offences have something to gain from it, that complainants come forward with spurious accusations to affect negative outcomes upon the accused. It’s important to remember that here in the UK, it’s estimated that only around 3% of rape allegations are false (and that there’s some dispute over what false might mean, taking into account allegations that are retracted or dropped by police). In fact, men and boys are much more likely to have been the victim of rape or sexual assault than they are to ever be falsely accused of perpetrating a sexual offence themselves. As for the ability of survivors to affect consequences in the lives of their perpetrators, figures released by the Scottish government in 2022 show the lowest conviction rates in a decade (just 51%). And those survivors who do see their perpetrators tried and convicted still may not feel that justice has been served. Sean Hogg, convicted [now acquitted] for the rape of a 13 year old, was originally sentenced to just 270 hours of unpaid work and supervision on the sex offenders’ register for three years. In July 2023, Glasgow United FC signed player David Goodwillie, despite a civil ruling which found him guilty of rape in 2017. It seems that leniency and the benefit of the doubt are more common than “being cancelled” outright.

Reader, imagine reporting rape. Try and imagine what that process involves.

I can’t tell you what I thought it might involve. I asked a lot of questions about the process. I wanted to know what every step would be. Because there was more than one step.

Reporting rape is not as simple as walking into a police station, stating what happened, and going through it with an officer (who believes you).

Aside: I think television drama must take some blame for this misconception (think of Aimee’s report of sexual assault in Sex Education, for example) where the process, for the sake of pacing, must be streamlined.

You don’t report rape just by going to a police station and sitting through one form with one officer. It’s not that easy, and nor should it be. As much as the process can be improved, as much as it should be more trauma-informed, it should still be a slow and measured process.

Importantly, complainants don’t make it to court with just their stories.

We all know that the police are there to find evidence of a crime, to follow the evidence until they reach a point where they gauge that they have sufficiently “proved” guilt. What we don’t all know, and what one only learns from experience, is that the police need to meet certain criteria just to investigate. A certain amount of evidence is needed before speaking to the accused. Then, the Crown Prosecution Service needs to see all that evidence to decide on a charge, that is, to decide what offence it is that will be put to trial. Those rare spurious allegations (and many legitimate reports too) fall at that first hurdle, with the police; painfully and simply because the behind-closed-doors commission of sexual offences and the blaming and shaming of survivors conspire together to create circumstances where more-often-than-not, the police are left without evidence, and only historic he-said-she-said accounts.

For an accused perpetrator to have gotten to trial, that means there’s not just smoke, there’s fire too. On the balance of probability, they did it.

But what we test at trial isn’t actually “innocence”, it’s how well guilt can be proven: that is, the thoroughness of investigation.

There are no winners in criminal trials. Pay-outs in civil cases don’t undo the trauma. Survivors lose their phones, their underwear and sometimes themselves, in working with the police and the CPS towards justice. Survivors are forced to undergo hours or days of (often blaming) questions. Survivors are made to feel that the burden of proof is more important than what actually happened.

Rape, much more than any other crime, is surrounded by myth. This makes it so difficult to disclose, even to family and friends — never mind the police. So much of my experience deviates from the stories we’re told about rape. Rape happens to drunk girls. Girls in short skirts. Girls in wrong, dark places, at the wrong time. Girls who fight back. Girls who come away bruised and bleeding, if not worse. We’re told that rapists are crazy, that they have “problems”. Rapists aren’t “from here”. Rapists are violent.

But in reality, most of us aren’t those “perfect victims” we’ve heard about. I knew my perpetrator (statistically, most of us do). I liked him when we met 18 months before. I wanted him to like me. I stuck around and sexted him even though I knew he had a girlfriend. I’d had sex with him before; twice, actually. Not just that, he was the first man that I had had penetrative sex with. Before he raped me, I believed (wrongly), that there was a good man under all the actions that stung. I had an opportunity to turn him away, to just not let him into my house, and into my bed, and that’s not what I did. I stopped saying no. I froze. I did what he asked me to do.

I’ve had two blocks of counselling with RapeCrisis, but to this day, despite all the help and support I’ve been given, I do still struggle with that issue of who was really to blame. I think I went to the police before I had had enough time to really accept that I am blameless. Certainly, at times, tacitly, I was made to feel that what I did or didn’t do that night might have given him the wrong impression, that a jury would never believe me. I was made to feel that while what he did was “unacceptable”, it perhaps wasn’t calculated enough to be considered rape. Writing completely candidly, if I could do it again, knowing what I know now, I probably wouldn’t report.

These one-off offences that we hear about, the stranger rapes and the opportunistic attacks by celebrities, these narratives ignore how there are often quite long and complex relationships between the perpetrators and survivors of these offences. Stranger, acquaintance, current/former sexual partner: these boxes, literally tick boxes on a form, made my experience of reporting rape much more difficult. There isn’t one word for who my rapist was to me.

There are nicknames now, for the things that he did to me in the months leading up to the rape. Ghosting. Zombie-ing. Breadcrumbing. I’m in two minds about these words. On one hand, it’s good to have a name for something; it’s a shortcut for disclosure, it makes, in theory, something easier to talk about. But on the other hand, are these words in some way dismissive, in that they normalise harmful behaviour? I worry when I hear other young women describe similar push-pull/on-off behaviour from their sexual or romantic partners. But I will admit, when I step outside of myself and look in hindsight at everything that passed between me and my rapist, I can see “how it looks”. Every other girl I know that’s a survivor is as bright as I am, as capable and funny and fierce as I am, but we were all told, even by each-other, to escape, to move on. We were all, in some sense, aware of a building pattern, and felt unable to get out before “it got to that point”. I look back at the things that I felt about the young man who would rape me, and I feel that I was pathetic, and wilfully ignorant. Why do I tell you this? Because, although we can say that ghosting hurts, or that breadcrumbing is a dick move, I don’t think we – and the institutions involved in justice – fully understand how deep the wounds from these actions can go. On the face of it, I was not alone; I had people to talk to about what was going on. But what men like my perpetrator somehow know is that people will only listen for so long. Then, you’re alone, and you want him to change, and you give him infinite chances while the cycle repeats, because the anger fades into sadness and declining self-esteem.

I think it’s fair to say that misogyny and sexual violence are two of the biggest issues facing the world today. The Baroness Casey review laid bare a police force that’s sorely lacking, not fit for purpose, and especially unsympathetic to survivors of domestic and sexual offences. Another report found trust in police is close to, if not at, an all-time low, and that public-police relations are dangerously stretched. A government advisor resigned this year, feeling unsafe and concerned about a lack of willingness to change. When we see pledges to take action on sexual violence, they seem to focus on the prevention of stranger rape, and how safe we are in public places, as opposed to, say, investment in charities like RapeCrisis and Survivors, or an overhaul of the sex education curriculum; where we might add lessons on rape myths or models on how to recognise and call out everyday sexism.

My hope is that this is rock bottom — that we can move together and turn our outrage into change. Organisations are already making a start. Through all the pain that’s come with acknowledging that I was raped, I have felt incredibly grateful to those who use social media as a force for good, especially Everyone’s Invited. The stories shared on the Everyone’s Invited website were invaluable in helping me realise that what had happened to me was not just bad sex, but perhaps, actually rape. My disclosure, my police report, the confidence I had in seeking mental health support, that all stands on the shoulders of thousands of anonymous survivors.

The Scottish government has taken significant steps this year. The Victims, Witnesses and Justice Reform Bill has put forward a package of proposed reforms to the existing criminal justice system, all of which could, in theory, improve the experience of survivors and the likelihood of conviction in sexual offences. It is important, though, to note that nearly all of these depend on the willingness of individuals to commit to trauma-informed practice, to receive further education about consent, trauma responses, and the lasting impact of trauma. EndRapeMyths has already launched a petition for this kind of education, focused, rightly, on jurors; research has demonstrated an unwillingness or uneasiness to convict for sexual offences. In October, a panel of judges decided that evidence of distress shortly after an alleged assault or rape will now be considered as corroborating evidence. None of these measures are nearly comprehensive enough, but they do represent a start, and we should give them the credit that they deserve.

I suppose that overall, my point is: change is difficult, and it’s not quick, but we can fight this. We can change the experiences of future survivors. We can make it so that we can say, not only do we believe you, but the system will too.

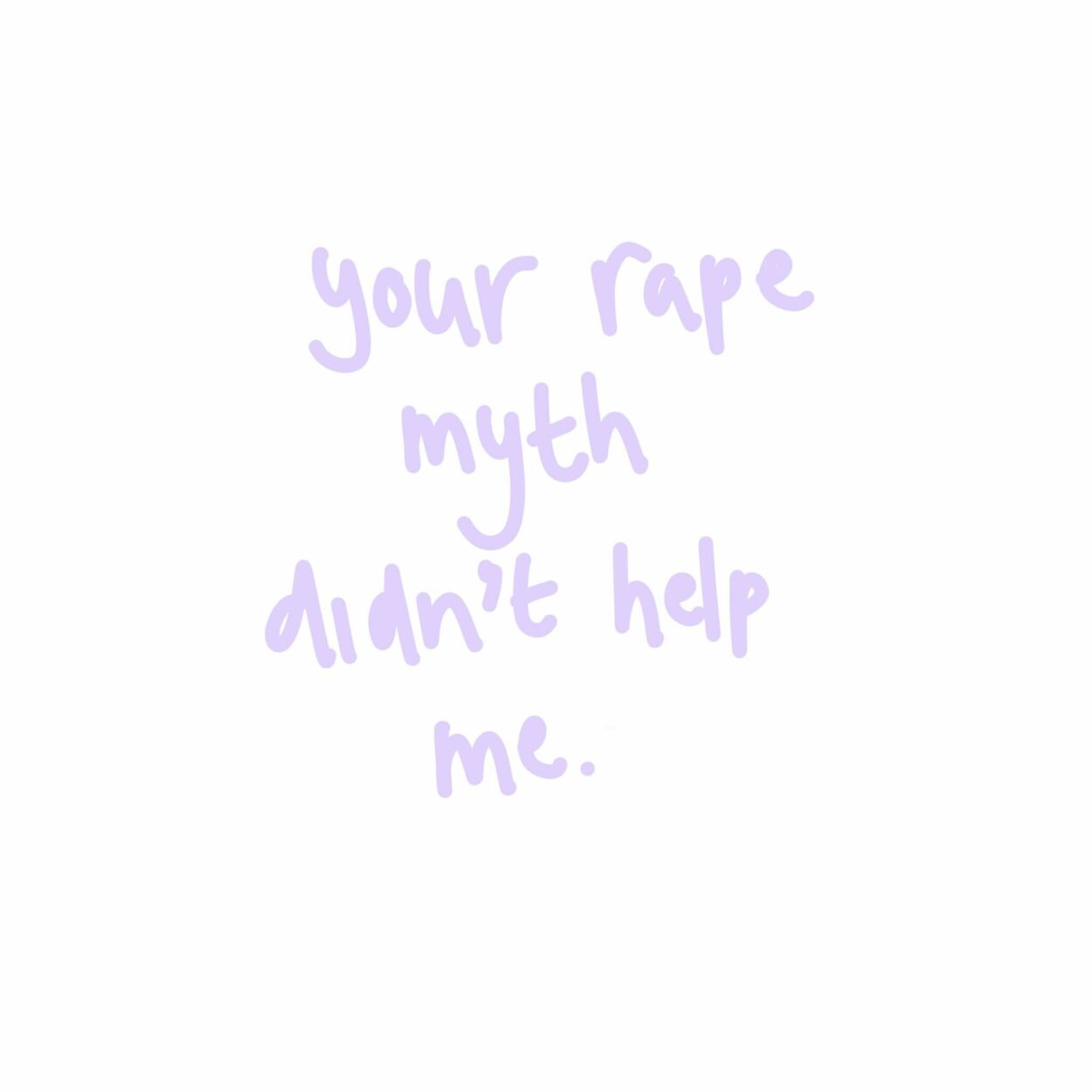

Header image by Peggy Mitchell, one of our wonderful graphic designers.