On March 6th, 2022, I attended a memorial protest at Scottish Parliament on the one-year anniversary of Sarah Everard’s murder. Several women spoke in her memory highlighting brutality of gender-based violence in the U.K and around the world, calling for the dismantling of the very systems that are meant to protect us but instead regularly create violence and fear.

In a dystopian time, we must be indulgent in our utopian fantasies

I walked away, feeling glad to have attended such a powerful memorial but nauseous as to the dystopian context of the world where such events have to happen.

This nausea is not a new feeling in times that often feel like some sort of political horror. The latest inhumanity of ‘The Hostile Environment’ via the Nationality and Borders Bill in the House of Commons in December of 2021 sparked this feeling. The bill perpetuates and extends the inhumane nature of the 2014 Immigration Act, as many have commented building an ‘internal border’ by creating purposeful distress in services of housing, education, citizenship etc. Article 9 of the new bill is perhaps most terrifying as it allows for a stripping of citizenship without warning or appeal, with threat to leaving one stateless. Such legislation demonstrates an intentional manufacturing of anxiety from elected officials, leaving us to feel we are living in a dystopia where any sense of empathy is lost.

Conversely, utopia is a concept with a rich intellectual history, finding place in critical theory as well as many works of fiction. Raymond Williams discussed it as ‘the conviction that people can live very differently, as distinct from having different things and from beginning resigned to endless crises and wars’. This conviction in times of distress becomes increasingly more difficult to hold – as less hope surrounds us to fuel its imagination. Therefore, presentations of utopia in fictions of literature or visual culture can often be the honeypot for these ideas.

Reading Ursula Le Guin’s The Dispossessed recently allowed me to indulge in these ideas as the novel describes an anarchist utopia, where citizens recognise that a lack of community means a lack of survival. The use of science fiction by Le Guin allows an expansion of what we think is possible in the realities of our own world – driving the conviction that Williams described.

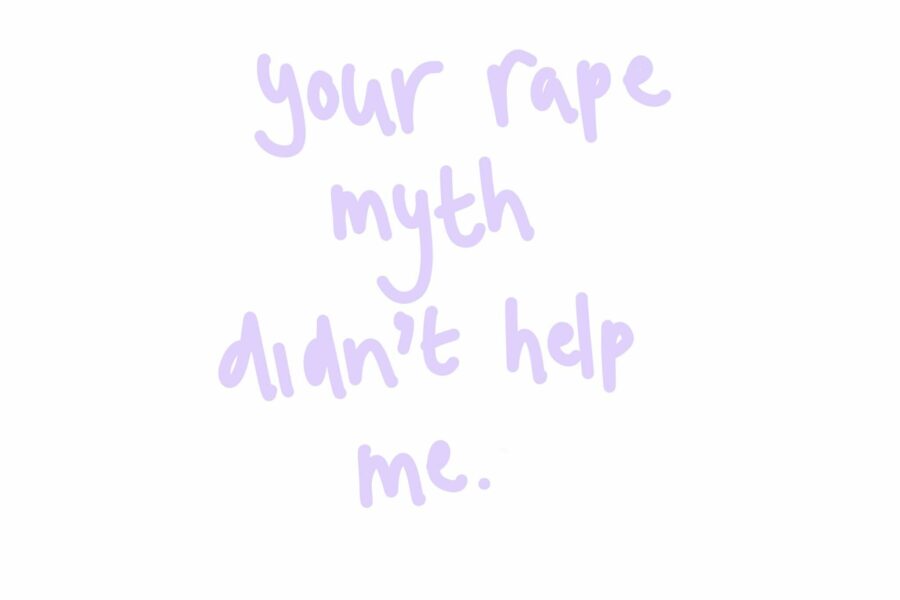

Returning to present-day dystopia with these ideas of utopian society in mind, alternate political imaginations are often dismissed as far too radical and thereby ‘indulgent’ of a utopian fantasy. Centrist political thought is often propagated as the sensible option, where any radical thinking is made synonymous with nonsense. However, the extremity of the horrors we can see require an alternative imagination, and action, of equal proportion. The extent of gender-based violence present in our world was brought to the foreground of my mind after attending Everard’s memorial and depicts this extremity aptly. Similarly, Home Sec. Priti Patel’s immigration ideology encapsulates the inhumanity at work in political structures.

Due to these extremities, it becomes easy to believe that ideas of utopia, such as those of Williams and Le Guin are to be kept as ideas. Discussions of a free immigration systems or a violence-free world can feel naïve and childish when these issues are so complex and corrupted, making the very thought of ‘utopia’ feel like an indulgent fantasy.

However, this indulgence is crucial. Ironically, the most powerful in our society are the closest to an experience of utopia as the rigid structures in place continuously benefit this small minority in all respects. Whilst benefiting from these institutional inequalities, it is in their interest to discourage these imaginations as any thinking that disrupts the status quo harms their personal interests. This privilege they hold so tightly, isn’t utopia as the very essence of the word and the ideas underneath it connotes a collective experience felt by all.

Therefore, succumbing to the narrative that radical thinking is indulgent, rather than necessary, is as dangerous as the idea of ‘common-sense politics’ that has often perpetuated our political horrors. So, whilst trying to muddle through the dystopias of today’s world, it’s not only allowed but highly beneficial to let ourselves immerse in what our collective utopias are, giving us conviction in organising the actions that can make them closer realities.

Leave a Comment