“The right to rest”, or resting as somehow radical, political, or subversive, are thoughts that I’ve been mulling over since January of this year. In my mind, January is a particularly fraught moment when it comes to rest, leisure, and relaxation. Conventional wisdom dictates that the new year is the time for setting goals and dreaming of future productivity — I’ll exercise more, I’ll finally write that article — but, in reality, lots of us are still hungover and languishing in the post-Christmas lull…

“Do you enjoy what you do?”: George Michael, Beyoncé, and the Right to Rest

It was on one of these lazy days, right at the very beginning of the year, that I first had the conversation which has inspired (and soundtracked!) this article. My friends and I were lounging in their kitchen, listening to music. Those of us present were taking advantage of university holidays, paid time off, or office closures, whilst our friends in hospitality and retail were already back at work — facing one of their busiest periods of the year. It was in this luxurious expanse of free time that my friend Joshua suggested we listen to “Wham Rap! (Enjoy What You Do?)” – George Michael and Andrew Ridgely’s 1982 anthem to unemployment, state welfare, and unashamed leisure.

For those of you less well-versed in the back catalogue of English pop duo Wham, I’ll give you a general idea of the song: twenty-something heartthrob George Michael, complete with a Princess Diana hairdo, gives his best white man approximation of R&B. George pleads with you, the listener, to consider if you “enjoy what you do?” before forcefully asserting that it is both cool and masculine to be “on the dole”. He even goes so far as to shout out the Department of Health and Social Security (or DHSS) by name. After all, he argues, who has more time to explore London’s booming club culture than the unemployed?

Hey, everybody, take a look at me

I’ve got street credibility

I may not have a job but I have a good time

With the boys that I meet down on the line

I said, D-H-S-S

Man the rhythm that they’re givin’ is the very best

Wham, bam!

I am a man

Job or no job, you can’t tell me that I’m not

Do you enjoy what you do?

If not, just stop

Don’t stay there and rot

The nearly seven (!) minute-long song gave us plenty of time to begin debating: underneath some of the more dated lyrics are Wham saying something radical? The early 1980s was a moment of unprecedented mass unemployment in Britain; “Wham Rap!” was released between two iterations of The People’s March for Jobs — protests against unemployment held in 1981 and 1983. When much of the British left was focused on the right to work, were George and Andrew being subversive or clueless?

“Regardless,” I remember saying, “I don’t think any major pop artist would release a song like this today.” Although workers were (and are) still reeling from the pandemic, pop culture appeared staunchly loyal to the idea of “the hustle”. We were still some months away from Kim Kardashian’s order to “Get your fucking ass up and work”, but ex-Love Islander Molly-Mae Hague had already made her infamous “Beyoncé has the same 24 hours in the day that we do” comments. The overwhelming message, especially for young women, was one of “girlbossing” — something I felt was unlikely to change, regardless of whether anyone received it positively.

The reason I’m writing this article now, instead of January, is not because I’m really behind on my New Year’s resolutions, but because it’s time to admit I was wrong. As of 21st June, Beyoncé — former icon of the “girl boss” doctrine — has called on us to quit our jobs. Admittedly, Beyoncé’s house banger “BREAK MY SOUL” is not as narrowly-focused as “Wham Rap!” — the verses call for a more extensive lifestyle revamp, beyond just giving up on employment. However, whilst George and Andrew are celebrating the joys of unemployment, Beyoncé is preoccupied by the indignities of work.

Damn, they work me so damn hard

Work by nine, then off past five

And they work my nerves

That’s why I cannot sleep at night

The right to rest and leisure is enshrined in both the Universal Declaration of Human Rights, and the International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights. However, both documents use the imprecise and slippery phrase “reasonable limitation of working hours”, leaving “reasonable” somewhat open to interpretation. As much as you might relate to Beyoncé’s objection to the 9-to-5, here in the UK “reasonable limitation” is manifest not as a limit on hours worked per day, but as hours worked per week. The UK currently follows the European Community Working Time Directive of 2003, which caps working hours at 48 per week. However, workers can opt-out of this limit voluntarily or if asked to by their employer. The right to rest and leisure also calls for “periodic holidays with pay”. Full-time workers in the UK are entitled to 28 days of holiday per year, but, depending on their contract, public holidays can be counted as part of those 28. England and Wales have eight permanent public holidays each year, Scotland has nine, and Northern Ireland has ten. But is this enough? Or is it time to reconsider our definitions of “reasonable” and “periodic”?

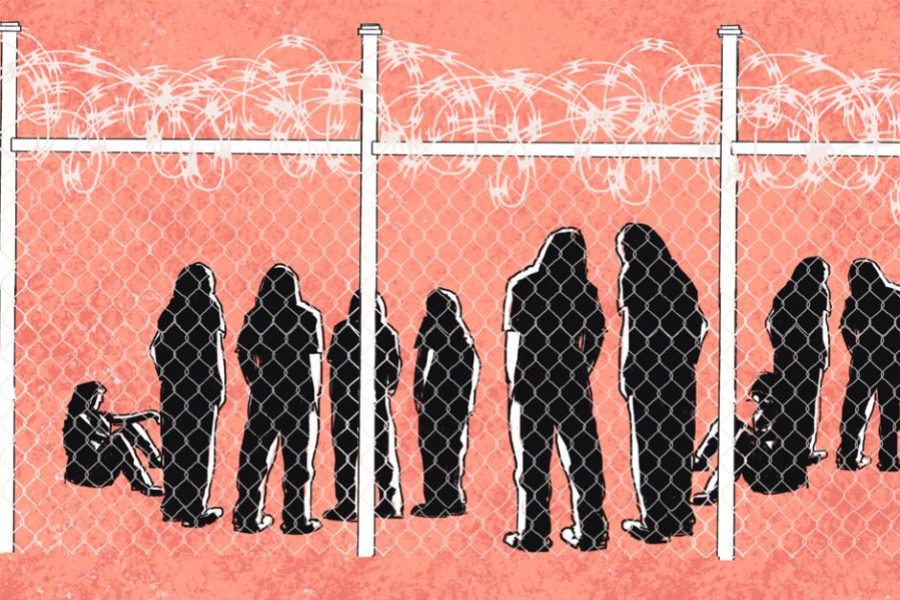

The Covid-19 pandemic brought discussions of work and rest into public discourse. It also threw the inequality of rest – who can rest and who can’t – into stark relief. Whilst plenty of us were at home, suddenly freed of our responsibilities, those so-called “key workers” found themselves working harder than ever, in dangerous conditions. If Beyoncé – an Oracle of Delphi for the twenty-first century – wasn’t proof enough that the last two years have caused a genuine societal reckoning with rest, then there’s plenty of evidence elsewhere.

In a Deloitte survey, released in May 2022, of the 23,000 workers aged 18-38 surveyed, 75% preferred hybrid or remote working, and work-life balance consistently came top of their priorities when choosing a new job. Anecdotally, employees are reluctant to return to the office full-time, as remote working provides freedom from the commute — a traditionally unpaid chunk of time out of one’s day. The UK is also currently home to the world’s largest four-day working week trial, with more than 3,300 workers across 70 companies taking part. Those involved represent a variety of sectors — from software companies to fish and chip shops — not just those in 9-to-5 environments. The scheme works on a 100:80:100 model: employees receive 100 per cent pay, for only 80 per cent of their regular hours, with the promise to maintain 100 per cent productivity.

All that being said, although our emergence from the pandemic has sparked conversation about rest, the right to rest appears to be largely missing from the political agenda — at least in the world of parliamentary politics. In January 2021, the Labour Party used the image of “key workers” to promise voters that they would fight to protect the 48-hour working week. In response, commentators were quick to criticise Labour for simply defending the status quo, rather than pushing for real change.

The demand for an eight hour working day, or 40-hour week, is nothing new here in Britain. In 1810, Welsh textile manufacturer and social reformer, Robert Owen, introduced the ten-hour day at his New Lanark Mill — inspired by his utopian socialist philosophy. By 1817, he was campaigning for eight-hour days for all, under the slogan “Eight hours’ labour, Eight hours’ recreation, Eight hours’ rest”. Two centuries later, Owen’s rallying cry is not a banner currently being flown by any major political party.

The Labour Party’s tweet also drew criticism due to the fact that, as recently as the last general election, Labour was campaigning for a four-day working week. Back in 2019, as part of Labour’s self-described commitment to “transforming lives, increasing fulfillment”, Shadow Chancellor of the Exchequer, John McDonnell promised to reduce average working hours to 32 per week, with no loss of wages, within the decade. He also committed to putting an end to the practice of opting out of the European Community Working Time Directive. McDonnell presented the reduction of working hours as an inevitability — one of the rewards of a modern, progressive society — which had been artificially stalled. The four-day week was a right that the modern worker had been denied, whilst the 48-hour week was a relic of the past.

“As society got richer, we could spend fewer hours at work. But in recent decades progress has stalled and since the 1980s the link between increasing productivity and expanding free time has been broken. It’s time to put that right.”

In that same campaign cycle, Jeremy Corbyn pledged to work with the leaders of the devolved governments to introduce four more days of paid holiday: St David’s Day, St Patrick’s Day, St George’s Day, and St Andrew’s Day. This policy was viewed by many as impractical or disruptive — even though, as Corbyn himself was keen to stress — the UK currently has the fewest paid national holidays of any G20 or EU country. Four more national holidays would not be an unreasonable indulgence that our economy would be unable to handle, but would simply bring the UK in line with our European neighbours.

Three years later, not only has all this mythic extra leisure time never materialised — it has been wiped from Labour’s agenda altogether. Last month, Keir Starmer confirmed that he had scrapped all pledges from the 2019 manifesto, in favour of “starting from scratch.” In his words: “the slate is wiped clean”. This is in spite of his promises during the 2019 leadership election, where he praised the manifesto as “foundational” and insisted that the Party must hold on to it going forward. On July 25th, Starmer announced that, under his leadership, Labour’s primary goal will be economic growth. He also stated his intent to make Britain “the best country in the world to start a new business”. Unfortunately, what this means for the work-life balance of those employed in Britain’s new businesses is yet to be discussed.

I can appreciate that at this moment, amid a cost of living crisis, the choice to publish an article about the right to rest might seem counterintuitive or even thoughtless. Across the country, people are working as hard as possible to make ends meet, and I’m suggesting we all have more days off! However, I truly believe that the right to rest and the right to live free from poverty are not mutually exclusive, but instead are two sides of the same coin. A good wage is one which enables you to support yourself and your loved ones, without having to work indefinitely until exhaustion.

In addition, by calling for regular hours of rest, I am also calling for regular hours of work. Research by the Living Wage Foundation has shown that currently 37 per cent of all UK workers are given less than a week’s notice of shift patterns and 7 per cent of working adults are told less than 24 hours in advance. This state of always anticipating a potential shift, out of financial necessity and fear of reprimand, is in no way conducive to meaningful rest and leisure time. If work can unexpectedly arise at any moment, then there is no true respite.

To return to the conversation which first inspired this article: should George Michael be canonised as a Left wing folk hero? Is “Wham Rap!” a radical anti-capitalist anthem, or does its “go on the dole and party harder” message reveal a failure to grasp the reality of being unemployed? Similarly, in “BREAK MY SOUL”, has Beyoncé successfully intuited the mood of her fan base, or are her calls to quit the 9-to-5 a bit “let them eat cake”? These are the type of silly, inconsequential questions I spend my rest time discussing: in the pub on a weekend; over tea and toast the morning after a big night out; or during a weekend trip away with loved ones. This time is for me, to use how I please, at rest or at leisure, and it is my right.

Ruby Hann, Politics Writer

Header image by Peggy Mitchell, one of our wonderful graphic designers.

Leave a Comment