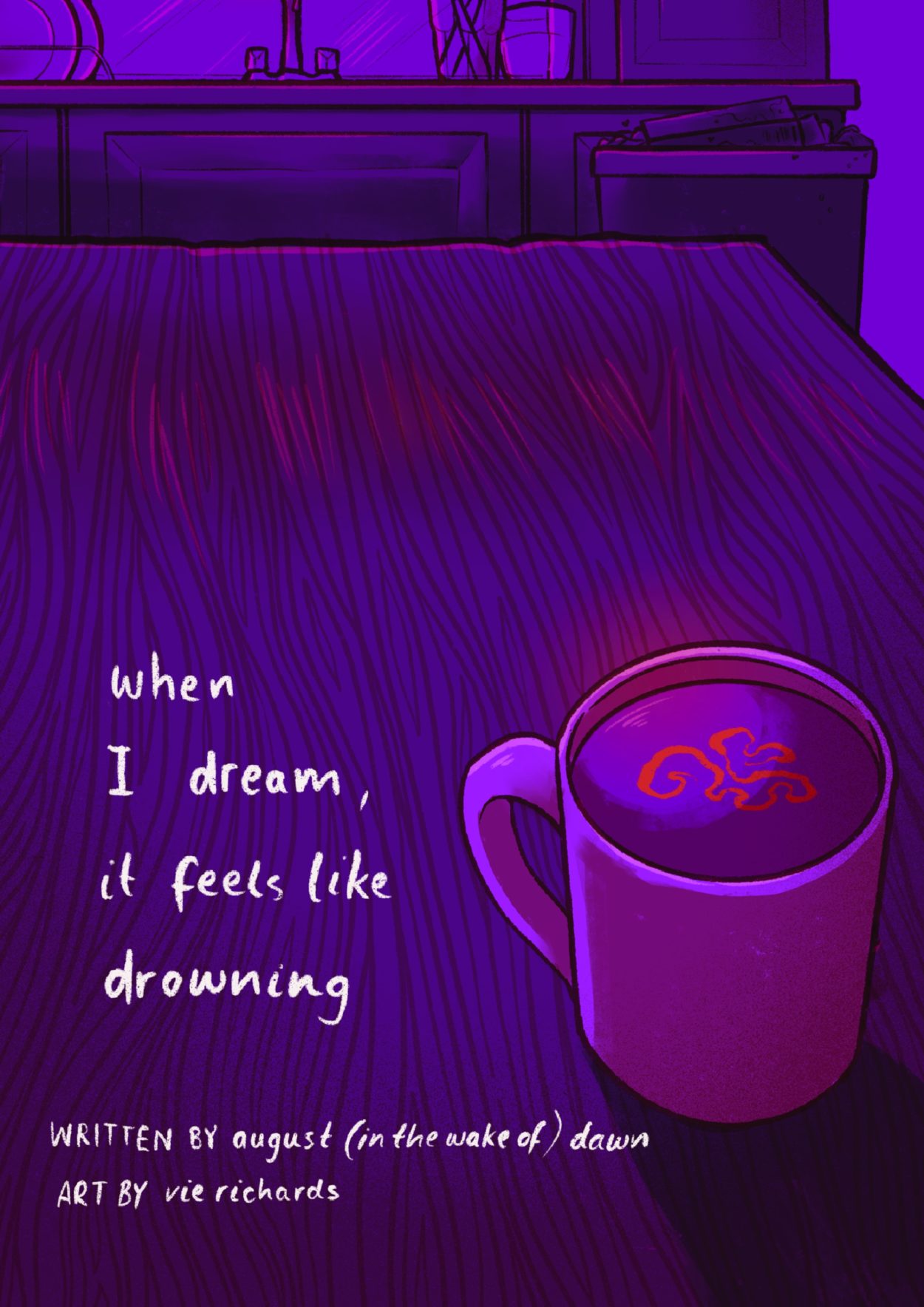

I carried out an interview with Door Ajar Comics after reading their first publication, WHEN I DREAM IT FEELS LIKE DROWNING. Their fascinating, heartfelt and brilliantly insightful answers explore inspiration for the work; personal experiences; narrative development; horror as a genre; readership, and much more.

WHEN I DREAM IT FEELS LIKE DROWNING: an interview

Door Ajar Comics is a queer-led, Edinburgh based comics collective consisting of august (in the wake of) dawn and Levi Richards. They explore themes of trans identity, queerness in the modern world and the overlap of mental health and faith in experimental fiction. WHEN I DREAM IT FEELS LIKE DROWNING is their debut work, a hallucinatory short comic that explores themes of dissociation and depression, that saw its print debut at Thought Bubble 2021.

What first gave you the idea? How did you then develop it into the final narrative?

AUGUST: A lot of DROWNING came from my own experiences with hallucinations, dissociation and depression. Most of the vignettes of the comic, from the girl looking in the mirror to the baby head (which came from a dream I had once), that marks the midpoint of the story, to the chair being pulled out by seemingly invisible hands, were scenes I’d been rolling around in my head, but I could never find something that allowed me to weave them all together. DROWNING came together after Levi and I met and started talking about making a comic together. We’re both interested in horror, especially psychological horror, and so I finally started hammering it all into shape, which eventually became the final comic.

What was the creation process like for you? Cathartic? Did you find it difficult?

LEVI: I honestly think I found the creation process easier than I have other comics I’ve made. This was my first time collaborating with a writer and I found that having someone else’s work to go off made it much easier to work through than when I script comics myself, because I’m not constantly second guessing the writing. In terms of content, I think because doing the artwork was such a drawn out process, I didn’t get the full impact of the horror or the dysphoria in the same way you would if you were reading the finished thing for the first time. You get a bit desensitised to it — it almost surprised me when we were first showing people and they were saying they found it genuinely scary!

AUGUST: As I said, I’d been trying and failing to tie all of these disparate scenes and images I had in my head into something cohesive and readable. Writing something for myself, especially a comic, isn’t the easiest because I end up feeling like I’m spinning in place, so being able to draft and then script DROWNING knowing that it was essentially a letter to Levi where I could pour all of the weird idiosyncrasies of my brain and knowing he’d get it and make something even more interesting out of it really propelled the process for me.

The use of colour is very powerful, as is the lack of words – creates a very visceral, eerie scene. Did you consider including more narration? What made you decide not to?

AUGUST: I did consider using narration, and the title actually comes from what was the first line of the comic in many of the drafts I’d written. I kept trying to find ways to dig into the girl’s head through narration, but I realised that a lot of the inspiration on the pacing of the comic were these long, uninterrupted and often silent shots in slow burn horror films that I loved – stuff like IT FOLLOWS, IT COMES AT NIGHT and THE VVITCH, especially. So, when I started to strip more and more of the narration away and started trusting Levi to convey that visceral eeriness through the artwork, it became really easy to let go of it completely and let the artwork stand on its own.

The repeated appearances of the abstract red lines throughout the story really caught my eye. Can you expand a little on what they mean to you?

LEVI: I think the whole time I really wanted to give the sense that there was something unnerving and off in the environment, like it has its own life that’s outside the main character’s control. For me, the really saturated unnatural colours, and the red lines especially, were to give this sense that the character isn’t quite in reality. I wanted to produce a bit of an uncanny feeling against the ordinary backdrop of the house, and also the sense of some other force that’s sort of moving and inhabiting the house, that the red lines embody.

Do you have in mind an audience you particularly want to receive your work? Eg a cis audience in the hopes that they come to understand gender dysphoria a bit better, or a trans audience who may benefit from being able to relate?

LEVI: Personally I think that it’s important as a trans artist to make art that’s aimed towards trans people. I think because being trans is really coming into the public eye and in a quite demonising way, trans media I’ve read/watched can sometimes feel like it’s trying to explain transness to people who might not understand it. And that’s definitely necessary and super important! It’s really vital to educate people, and I think art is a great way to help people understand other perspectives. That said, I also think it’s valuable to have trans art that specifically is aimed at other trans people, so you can delve into the experience a bit without getting bogged down in defining your terms for people who haven’t experienced it firsthand. I’m really interested in the idea of trans horror, and what makes something trans horror, and how that can be executed in a valuable way — how you can make something that speaks to the trans experience without just making something retraumatising or too uncomfortable to read. With DROWNING, I was hoping we could nail that level of distance between ‘this is something I, as a trans person, can relate to, this is cathartic for me and speaks to my specific anxieties’ and ‘this hits too close to home, what’s the point of me reading about horrific stuff that I already have to deal with the anxiety of every day’. I’m hoping that by making DROWNING slightly more abstract in the way it presents dysphoria, it makes it more readable for trans people. That said, I think the comic is as much about isolation and mental illness as it is about transness, so there’s some room for all kinds of people to relate to it.

AUGUST: In many ways, the only audience I had in my head while writing was Levi. The funny thing about writing comics is that the audience rarely gets to see the words of the script, much like the audience of a film doesn’t really have a sense of what the screenplay says unless they seek it out. For me, it was all about getting this weird thing I had in my head out onto the page as words in this strange letter to Levi and letting him run it to the finish line with his artwork. From there, I was just happy to have a real comic with our names on so that we could put it in peoples’ hands.

As a person who experiences gender dysphoria, I found it very real, very moving. Had you encountered much art depicting feelings of dysphoria prior to this? Did you have any particular inspiration for it?

LEVI: I think the video game ANATOMY is one we were definitely both massively inspired by. It’s a haunted house video game made by Kitty Horrorshow (who is a trans woman) that uses body horror and glitching houses to sort of explore that feeling of being uncomfortable in a place that should feel safe. More generally I’m massively inspired by haunted houses and horror stories — Mexican Gothic, Things We Say In The Dark, The Dangers of Smoking in Bed, anything by Shirley Jackson — so I enjoyed putting a trans spin on that.

AUGUST: Yeah, ANATOMY was a big one for me in the way it can speak to a specific experience of dysphoria without explicitly being about that in the text. It’s abstracted through the lens in which it portrays the story. When it comes to horror, I often gravitate towards film, so the films I mentioned previously, as well as films like UPSTREAM COLOUR, YOU WERE NEVER REALLY HERE, ANNIHILATION and the works of David Lynch were all swimming around my head as I was writing. They’re all very slow burning, meticulous looks inside the heads of very troubled individuals that eschew a grounded reality for a more twisted look at their perception of the world. I also found myself re-reading ZERO, a comic written by Aleš Kot, around that time which has always been a massive inspiration for me.

The final embodiment / figure – is that something that already existed visually for you? Or was it intentionally created for the story?

AUGUST: The figure at the table was a strange one, because I knew the story needed a button. Different drafts portrayed that scene in different ways, but none of them really sat right with me. I had those two final lines (“Your unravelling. You’re unravelling.”) in the narration at different points in different drafts and it felt like the right note to end on. It wasn’t until I took a step back and let Levi work his magic that I saw the ending come into view.

LEVI: I had a little bit of a tricky time visualising the monster, but I took inspiration from those sort of white gangly mysterious humanoid figures (kind of like Slenderman) you see in mocked up cryptid photos on the internet. The main thing that I added was the duct tape — August had the idea at the start of having duct tape stuck over the mirror where the character’s eyes would be, as if she couldn’t bear to look at her reflection properly, and I turned it into something that ran all the way through. Because so much of the haunting was to do with her reflection, I wanted to give this sense that the character’s own insecurity was chasing her in the form of this thing she’d used to avoid looking herself in the eye.

What does the horror genre mean to you personally?

LEVI: I’ve been really fascinated with horror for a really long time! I loved Stephen King as a teenager and now I read a lot of short horror stories, and am writing my dissertation on queer horror. As someone who’s dealt with anxiety, OCD, and intrusive thoughts for a long time, reading horror feels like a way to sort of reclaim all those anxious, scared feelings in a way that feels a bit more manageable. Writing horror especially felt like a great way of using unpleasant thoughts and an anxious mindset to my advantage, by turning them into something I can control, and so sort of take the power out of. I’ve read some horror about mental health and anxiety as well and found it really cathartic, so I hope our comics can do the same thing.

AUGUST: I saw a lot of now-classic horror films when I was far too young for them. I grew up in the 90s and was constantly stealing my dad’s VHS tapes of films like ALIEN, PREDATOR, THE EXORCIST and the like. They left a heavy impression on me and I ended up being that weird teenager seeking out films that were far too dark and heavy for me to be realistically watching at that age. It wasn’t until I started questioning my gender and after I came out as trans that I started to see the link between the horror genre and the queer experience. We’re all the lone survivor at the end of the slasher movie just desperately clinging on to the last shred of hope that we’ll make it out of all of this alive, and though we know we’ll never get back the life we had, we hope we’re stronger for the horrors we’ve experienced.

What would you like to say to someone who reads the comic and relates to it?

AUGUST: I don’t want to leave you with empty platitudes like “It Gets Better” or anything like that because I’ve never felt very comforted by that kind of ambiguous looking to the future. What I will say is that there are more people than you think going through similar experiences as you, and the best we can do for each other is to be there for each other. I think the saddest thing about DROWNING is that it’s the story of a girl all alone, not able to face the darkness within her all by herself, and whether or not she succumbs to it is something we left open, but I’ve been there. I’ve stared that darkness in the face and I’m happy to say that I’m still here only through the grace of the people in my life who can support me. It’s small comfort sometimes, but sometimes that’s all that tips the scales. And, maybe, we’ll be able to do that on a scale that does make things better, but right now it’s all about being there for people in your lives in whatever ways you can.

Leave a Comment