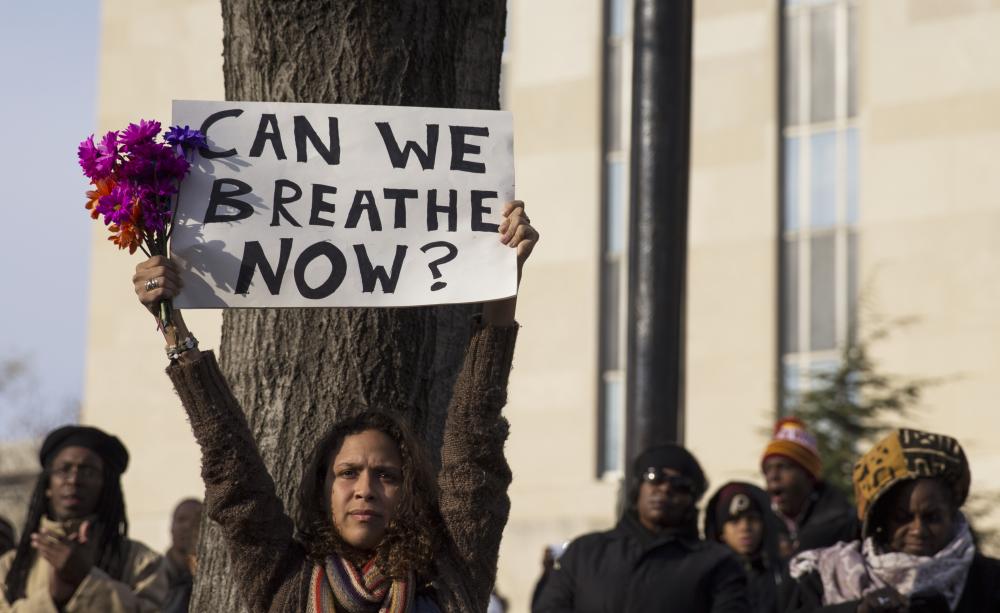

White environmentalists, we have work to do. here has been a resounding silence from so many in the climate movement over the last few weeks. I’ve seen people I used to respect who are vocal about the destruction our society inflicts on the environment suddenly become silent when BIPOC, but particularly Black people, are murdered without consequence. To better understand this lack of solidarity with the Black Lives Matter movement, we need to go back to the environmental movement’s origin. Newsflash: it’s steeped in racism…

The Racist History of the Environmental Movement

Madison Grant was a wildlife zoologist and founded the first organisation dedicated to preserving California redwoods and American bison. Part of a Manhattan aristocracy in the late 1800s, his group of conservationists was instrumental in helping create America’s national parks, forests and public access lands. Thinking that he doesn’t sound too bad yet? Well alongside championing the idea of environmental stewardship, he also warned of the “decline of the Nordic people” in his books such ‘The Passing of the Great Race: or the The Racial Basis of European History’ published in 1916.

His writing had significant influence on the American Immigration Act of 1924, which heavily restricted immigration from Africa, Southern and Eastern Europe and entirely banned immigration from the Middle East and Asia. In case you need any further persuasion of how utterly terrible his views were, Hitler called the book his “Bible” which has lent the text notoriety on the far right. Norweigan terrorist Anders Brievik credited Grant’s writing as the inspiration behind his murder of 69 left wing campaigners.

Another pivotal environmentalist, John Muir, was the co-founder of the campaigning organisation Sierra Club; now one of the largest environmental groups in the US. He described indigenous people as “dirty”, “all together hideous” and said they “have no right place in the landscapes” and he was “glad to see them fading out of sight down the pass”.

It was Muir’s narrative that led to the homes of indigenous people, in what was then known as the Ahwahnee Valley, being burnt to the ground in December 1850. A group of white vigilantes razed the valley that the Ahwahneechee people had called home for centuries to ashes, and forcibly removed its residents. Twenty three were killed and the survivors never were allowed to return. The following month, the Governor of California received special state funding to “punish offending tribes” and also renamed the land as the Yosemite Valley, with the fight against the Native peoples being dubbed “a war of extermination”. The US military had a presence there for a decade afterwards to ensure the native people did not return. When President Roosevelt ordered the land to become a national park, John Muir and his conservation work became synonymous with a national geographic treasure; the bloodshed of natives washed away from the land. In Muir’s writing, he described the park as “pure wildness” and where “no mark of man is visible upon it”, completely erasing the indigenous people’s history there.

A painting of The Ahwahneechee People

Despite public opinion to the contrary, Muir’s conservation strategies proved far less effective than those of the Ahwahneechee people, whose intimate knowledge of the landscape had been pivotal in creating the persevering landscape the general public were suddenly all rushing to visit. Their strategic use of rotational fires created grassy openings that improved biodiversity and helped plants thrive. However, Muir believed that “fire threatened God’s creations” and forbade all fires in the national park. More recent studies found that Muir’s approach not only decreased the diameter of trees (meaning they grew smaller) but also that the area’s biodiversity was markedly worse and was more vulnerable to floods and widespread wildfires. To this day, approaches like Muir’s are considered among best practice across many places in the world.

John Muir and Theodore Roosevelt in Yosemite.

In 1972 the Sierra Club polled all members on their opinions on including a focus environmental issues linked to the poor and ethnic minorities in their campaigns, 40% strongly opposed the idea and only 15% were in support. In 1990, leaders of US environmental justice movements wrote a letter to the main environmental organisations calling them out for their lack of work addressing the environmental struggles faced by communities of colour. This prompted them to hire non-white people, some for the first time, and adopt an increasing environmental justice approach. At this time, less than two percent of the 745 employees of the main environmental groups like the Sierra Club, Friends of the Earth and the Natural Resources Defence Council were non-white.

This history has left a lasting legacy that is still perpetuated by environmentalists. Still to this day, messages about the climate crisis often imply that everyone will face the consequences equally, but due to race, gender and economic disparity; this couldn’t be further from the truth. The climate crisis disproportionately impacts the Global South, despite contributing to global greenhouse gases significantly less than those in the Global North. Racist narratives are still peddled by mainstream environmental movements. WWF’s World Environment Day 2020 post included a video centring the issue of population growth in the Global South as the cause of the climate crisis. If you want to learn more about why this narrative is not only disproved by facts, but inherently racist, read my previous piece here.

The now deleted WWF video peddling racist narratives.

Extinction Rebellion have also come under fire after some actions that did not consider the impacts of their actions on low-income, predominantly non-white communities, one example being the action at the Canning Town tube station in London.

Including a climate justice narrative when discussing environmental issues does not “weaken” the message of tackling the climate crisis, rather it brings more people on board. We need to widen the definition of what an environmentalist looks like in order to create solutions to the climate crisis that benefit us all.

Learn more about intersectional environmentalism and sign up to the Intersectional Environmentalist Pledge here: https://www.instagram.com/p/CAvaxdRJRxu/?utm_source=ig_web_copy_link

Leave a Comment