New figures released last month by the UK Health Security Agency, to mark the beginning of National HIV Testing Week (7th-13th February), have revealed the changing form of the HIV epidemic in the UK. For the first time in a decade, the number of new HIV diagnoses in England is higher among heterosexual people than gay and bisexual men…

Not Funny Then, and Not Funny Now: Responding to the Changing HIV Epidemic

New figures released last month by the UK Health Security Agency, to mark the beginning of National HIV Testing Week (7th-13th February), have revealed the changing form of the HIV epidemic in the UK. For the first time in a decade, the number of new HIV diagnoses in England is higher among heterosexual people than gay and bisexual men. Although the latter are still more impacted by HIV relative to their population size, in 2020 49% of new diagnoses were of heterosexual people – compared to 45% for gay and bisexual men. These findings were reported by a number of major news outlets, including The Independent and The Guardian, but I first encountered this headline in the form of a tweet by HIV and sexual health charity Terrence Higgins Trust. At the time of writing this article, the tweet – posted 7th February 2022 – has over 12,000 likes, 6,000 retweets, and, most importantly, 3,500 quote tweets.

For those of you not well-versed in Twitter, a quote tweet allows you to share a tweet to your followers, with your own commentary added. It is the ideal medium for a sassy retort. Has some out-of-touch columnist written something you disagree with? Simply quote tweet their article and then all your like-minded friends can see your quip plus the original tweet you’re making fun of. The problem is many of the quote tweets of the Terrence Higgins Trust press release follow this established pattern of Twitter discourse. Scroll through and you’ll see the same jokes come up again and again: “maybe heterosexual people shouldn’t lead such an immoral lifestyle”, or “it’s time for a ban on heterosexual people giving blood!” I later found similar sentiments shared on Instagram and TikTok.

Let me start by saying, it’s not that I don’t get the joke – it’s that I just can’t find them funny. I understand the format: queer people repackaging homophobic talking points to throw them back at straight people. These jokes are a time-honoured tradition amongst marginalised communities, and when they work they really work! However, what makes these types of jokes funny in other contexts is that they’re punching up. A joke about how Disney Princess films are pushing a heterosexual agenda onto children is poking fun at one of the wealthiest media conglomerates in the world. By contrast, a joke about heterosexual people being diagnosed with HIV is just perpetuating old-fashioned HIV stigma. I’m not a completely humourless feminist – but I am a spoilsport.

Not only do I understand the format of this joke, I also understand who the authors of these tweets think they’re targeting. If you yourself have ever made a similar joke, I’m sure you think that you were punching upwards. I bet you were most likely imagining a cisgender heterosexual man. Maybe it’s the man who threw homophobic slurs at you on the bus, or a philandering ex-boyfriend who never wanted to wear a condom. You might have been imagining them to be a white man, with all the privilege that affords them. You probably didn’t think much about this man’s class background or immigration status. But this imaginary man, invented for the sake of a punchline, obscures the true demographics of HIV diagnoses in the UK.

The 1980s HIV/AIDS pandemic was allowed to become the “AIDS Crisis”, as we remember it today, precisely because it predominantly affected marginalised people: queer people, disabled people, sex workers, drug users, immigrants, and people living in poverty. In the United States, the Centre for Disease Control infamously described the people most at risk of AIDS as the “Four Hs” –“homosexuals, heroin users, haemophiliacs, and Haitians.” In London, the local branch of international AIDS activism movement ACT UP floated condoms over the walls of Pentonville Prison, to protest that incarcerated people could not access adequate treatment or preventative measures. Meanwhile, by the mid-80s, Edinburgh – Clitbait’s founding city – was known as the “AIDS Capital of Europe”, largely due to the prevalence of heroin users. From the first years of the epidemic, heterosexual people were failed by government inaction, just as queer people were.

The demographics of people living with HIV have evolved since the 1980s, but marginalised people continue to be disproportionately affected. In 2012, people from “sub-Saharan Africa” (to use the original language of the report) accounted for 1.8% of the UK resident population but comprised 34% of HIV diagnoses that year. More recent research by The Terrence Higgins Trust found that women are less likely to be offered HIV tests by sexual health providers, and that in 2019 over one-third of Black women of African heritage missed out on an HIV test in a sexual health clinic in England. In Scotland, sexual heath charity Waverley Care, found that during the first two years of Scotland’s PrEP programme (2017-19), just 0.4% of those who accessed the drug identified as African or African Scottish. A 2021 report by the UK Health Security Agency similarly found that in a PrEP trial conducted in England between 2017 and 2020, 76% of the 24,000 people accessing the drug were White and only 1.5% were Black African. (PrEP, or pre-exposure prophylaxis, is a medication that HIV-negative people can take to dramatically reduce their risk of contracting HIV.)

Other groups who continue to be disproportionately affected by HIV include drug users and those navigating the British immigration and asylum system. Waverley Care has found that in Greater Glasgow and Clyde, diagnoses among people who inject drugs have risen: since 2015, there have been 189 diagnoses, compared to an average of 10 per year prior to 2015. Migrants and asylum seekers face hostile policies which curtail their access to healthcare and force many into destitution. Migrants living with HIV are more likely to be diagnosed at a later stage, and those detained in immigrational removal centres frequently experience greater illness as a result of their detention. Finally, women are considerably less likely to be prescribed or otherwise access PrEP. In 2021, just 4% of those on NHS England’s PrEP trial did not identify as gay or bisexual men.

Now that we’ve complicated the image of the heterosexual HIV-positive person, let’s return to our imaginary cisgender, straight, white man. The one that most of the tweets I encountered were aiming to making fun of. Even if this person exists – and, just statistically, I’m sure that they must do – their relatively privileged identity doesn’t protect them from the misinformation, fear, and prejudice that surrounds HIV. HIV-positive people can face both stigma within their interpersonal relationships, and discrimination in workplace or healthcare settings, despite the latter being illegal in the UK thanks to the Equality Act. Across the world, HIV-positive people also face barriers to travel and migration due to their status. Several countries ban their entry entirely, or deport foreign nationals who are found to be positive, whilst plenty more restrict applications for students, work permits, and residency permits.

Heterosexual people are also far more likely to be diagnosed at a late stage. “Late stage HIV” is a term used to refer to what was once more commonly known as AIDS. By this point, the patient’s immune system has been significantly weakened, leaving them vulnerable to infections and at a higher risk of developing certain forms of cancer. In 2020, 55% of heterosexual men were diagnosed at a late stage, in comparison to just 29% of gay and bisexual men. Patients with late stage HIV may find their illness impacts their ability to work and complete everyday tasks, which in turn can result in them experiencing ableism and poverty. These are all examples of oppression that we as feminists, and as queer people, should learn about and challenge when we encounter them.

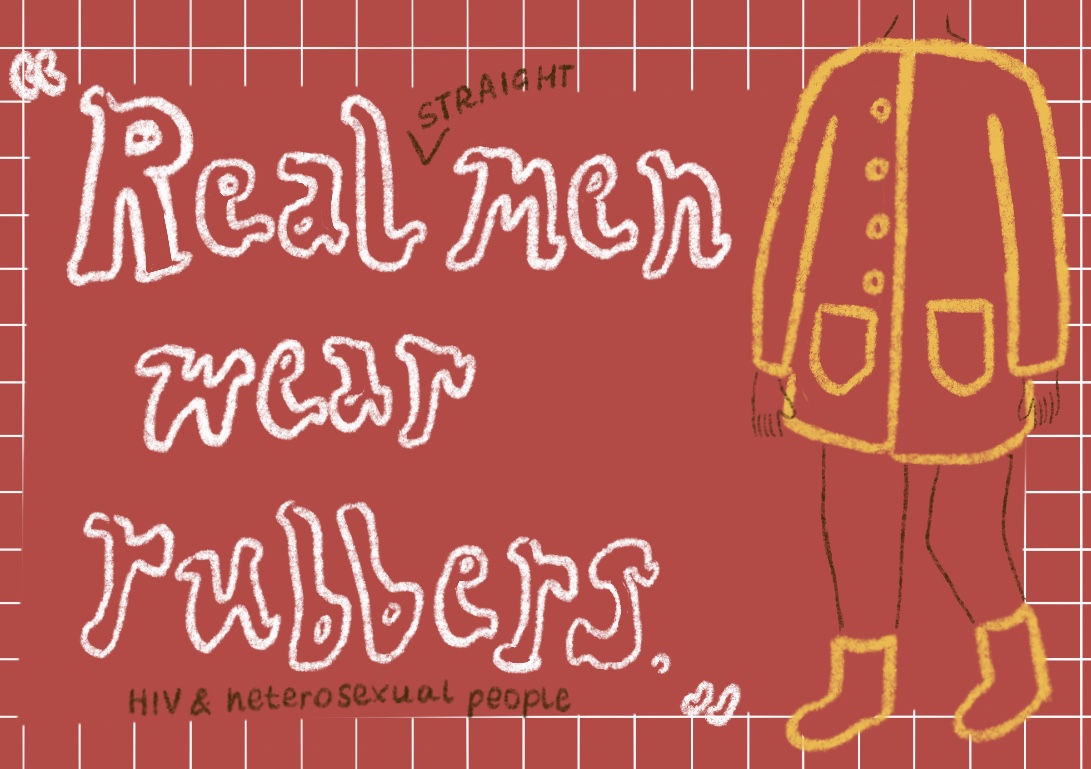

My intention when writing this article was not to scold, but to educate with empathy. I chose not to include any specific examples of these jokes within the article precisely because I didn’t want to focus my criticism on any one individual. After all, who hasn’t occasionally missed the mark when trying to discuss public affairs – especially about a topic this emotional? I truly believe the people who made these jokes did so from a place of frustration and hurt, rather than any real desire to perpetuate HIV stigma. For example, jokes about banning straight people from donating blood may be thoughtless, but they do serve to highlight the discrimination gay men currently face when trying to donate. I also understand that it feels good to indulge in jokes about your oppressor – whether a real person or an imagined figure – and I empathise with the rush of wanting to provide the fastest and funniest commentary on social media. But ultimately, even if they are not intentionally malicious, these jokes uphold rather than subvert the current power structure. A far more radical position would be to instead stand in solidarity with all people with HIV – to promote education and safer sex practices, dismantle discriminatory legislation, and fight stigma.

Ruby Hann, Politics Editor

Header graphic by the wonderful Lucia Villegas

Leave a Comment