Last year I spent a portion of my gap year in Pakistan. One day I attended a lecture on Jinnah, the founder of the nation. I remember shivering in the freezing lecture theatre. I remember meeting friends outside in the garden. I remember hitching a ride home with a family friend. I don’t remember anything out of the ordinary from that day.

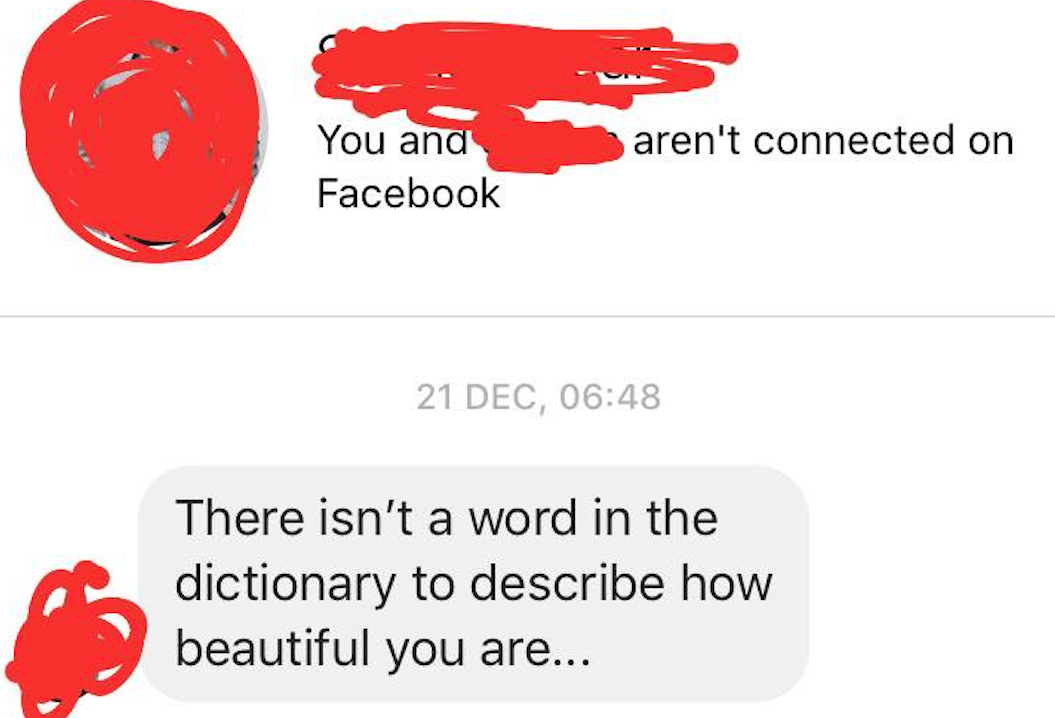

The next day stands out in my memory as being extraordinary. I woke up and reached for my phone for my usual fifteen minutes of sleepy scrolling in bed. I saw a notification for a new message request. The message went as follows:

It was not the first time that I had received a message from a creepy man. In fact, all of my brown female friends have received similar messages from our male counterparts. But this was slightly different. Up until this point, nobody had seen me in real life. Encounters with these men never escaped the virtual realm. So while this message was slightly concerning, I didn’t think much of it because the chances of running into this man again were slim to none.

At least that’s what I had thought until the following month when another message popped up from the same man. It was a photo of me, taken outside the same lecture theatre on a different day:

This time I was frightened. This person had been near enough to take a picture, near enough to speak to me, to touch me. For the next few days, I felt slightly uneasy leaving my house.

A boundary had been crossed which made it more difficult for me to occupy public space without feeling insecure.

But when I relayed the events to my family and friends members, they shrugged it off with the explanation, ‘it happens over here’. It was only my British friends whom echoed my feelings horror and disgust.

I couldn’t fathom the reason for the stark difference in reactions. Why did my brown friends normalise this behaviour while my British friends shunned it?

The question played on my mind for months, even after leaving Pakistan. However, it became clear to me that an elementary comparison of the societies was counterproductive. Cultural attitudes are fostered by different experiences and stimuli, meaning that I could not judge Pakistani men by my ‘western standards’. This doesn’t mean I’m an apologist for harassment, I’m merely trying to explain why it exists in a South Asian context and how we can amend it.

The archetypal love story which has pervaded the poems, songs, myths and visual art of the Indian subcontinent, is of that of a man seeking the love of a woman by stalking her. Most recently, and perhaps most potently, this storyline has been energetically re-worked by Bollywood. Film after film has narrated the epic saga of a girl who said no until she was forced to say yes. The story is so generic that even the sharpest minds, those most aware of misconduct, are numb to it. The formula appears so successful, that it’s no wonder that men have adopted this approach off-screen.

However, this narrative owes its success to belief which is deep rooted in subcontinental psyche: that a man is entitled to anything he desires. Including any woman. It is this cultural mindset that has wrongly understood and accepted harassment as flirting.

There is no single solution to the problem. But there are some steps which may begin to introduce change. Firstly, allowing women to presume an active role and voice. Depicting narratives on celluloid where the girl chooses the boy that she wants to be with (or chooses no boy at all), may inspire women to make their own choices off-screen. Coupled with the vital teaching of young boys consent will hopefully encourage a different environment and behavioural standard across the subcontinent. One which holds respect at its core.

I appreciate that these suggestions are fraught with complexities but without advocating for their implementation, we will remain passive to the more harmful and problematic aspects of our culture. I hope that in the future I won’t have to tell my daughter: ’it happens over here’.

Leave a Comment