The algorithms that decided both the SQA and A-Level results have further exposed the class divide in our education system. It is past time we re-think private education. British education is a two-tier system. There are those who can afford to pay for the education they deserve, and those who cannot…

Independence: Why private schools play no part in a just future

Just weeks after the Tories peddled the fate of disadvantaged students in an attempt to guilt-trip teachers back to work, they almost scuppered the life chances of a generation of disadvantaged children. The Scottish Qualifications Authority amended 133,000 recommended Highers grades, a large majority of them downwards, with students from the most deprived backgrounds affected worst. The pass rate for those students was cut over 15 points, from 85.1% to 69.9%, while the cut for the wealthiest pupils was only 9.8. The algorithms that decided both the SQA and A-Level results have further exposed the class divide in our education system. It is past time we re-think private education.

British education is a two-tier system. There are those who can afford to pay for the education they deserve, and those who cannot.

There is no doubt that private schooling brings huge privilege to those who receive it. If it didn’t, why else would parents fork out an average of £14,102 each year for their child’s education? Despite this being a somewhat controversial debate amongst the left, I personally cannot think of one rational defence for how pivotal a parent’s financial assets are in dictating the quality of education their child receives.

According to the Independent Schools Council, a UK family needs an annual income of at least £150,000 to send two children to private school. Recent research estimates that the UK median household income is £29,600. After we’ve spent months praising the work of our country’s nurses, carers, and shelf stackers, none of whose wages could afford private school places for their children, how can we now turn around and declare their children less deserving of quality education?

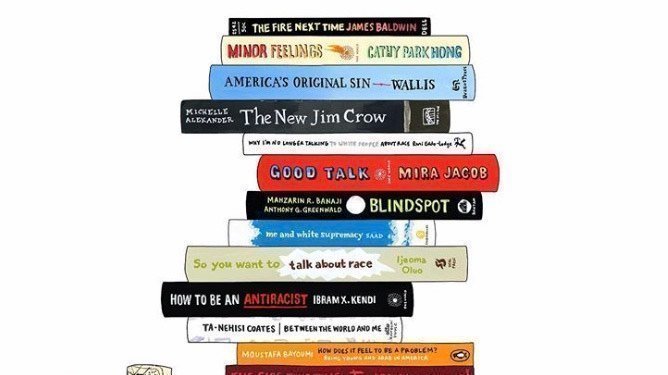

Due to extensive budget cuts over the last decade, state school-educated children are learning from overstretched teachers, in bigger classes and with fewer opportunities than their private school-educated counterparts. The latter receive better quality education, are more likely to receive higher grades, and are consequently three times more likely to attend a Russell Group university than their state-educated peers. Furthermore, private schools funnel children of wealthy families into the country’s top jobs. Just 7% of students are educated privately in the UK – yet private school students compromise 74% of senior judges, 61% of doctors, 59% of civil service permanent secretaries and 54% of senior journalists.

Neither of my parents went to university. Having a parent who is familiar with the admission process, or a well-connected alumnus of the university you’re applying to, unarguably brings further advantages. As my friends asked their parents for guidance on dissertations or referencing systems, I had to work it out for myself.

One option, the renationalisation of private schools, would mean redistributing the wealth and land hoarded by private institutions, so students from all backgrounds can access quality teaching and opportunity. In Finland, for example, charging tuition in basic education is prohibited by their constitution. It scores highly on the internationally recognised Programme for International Student Assessment (PISA) for science, mathematics and reading, and its fifteen-year olds generally outperform those of countries with private education. The gap between those who perform well and poorly is far smaller, and there isn’t a correlation between wealth and educational outcomes.

Of course, there are still changes that can be made to private schooling without their complete abolition. Adding VAT to private school fees, a policy generally supported by the electorate, would raise £1.5 billion for the Treasury. Removing private schools’ charity status would also bring huge benefit to the taxpayer as, unlike state-funded schools, they are exempt from many taxes on services and purchases. An argument against this is that having the education of wealthier children subsidised by the state is a drain on resources. This is resolved by simply taxing those same parents higher rates to contribute to their child’s education that way instead. Of course, this would mean the money would not go to solely benefit their own child, but help deliver a quality education to every child, thus improving society immensely.

Whilst the necessary reform to our education system extends far beyond investment in state schools, access to higher education is a key way for children to escape the cycle of poverty. The fight for equal access to quality education is a fight for social justice, and essential to improve our society. Now more than ever, we need to re-evaluate our education system to be fairer and provide equal opportunity for all.

Leave a Comment