In an antiquitous world, where social distancing wasn’t yet the de facto theme of interaction, I used to get dressed up to go dancing with my friends. Being a young, privileged, educated woman, with a budding feminism and progressive view of the world, I acted in accordance with my own agenda. With that in mind, there was a hostile undertone. When looking in the mirror, measuring my drinks, dancing in the middle of the dancefloor, I would slowly orientate myself towards someone else’s objective.

Bodily Intrusion: Anger towards the Inner Male Gaze

Behind my own eyes there is a second pair, one belonging to a system of male hierarchy that’s seeped in from all angles, one proving tricky to unhook.

‘Internalised misogyny’ is a term coined over the last 20 years of feminism; a form of oppression conducted by the subject themselves. It’s sexism, in its most villainous form, having coerced women to subordinate themselves, and implicitly continue to preserve the patriarchy. Worse still, it’s putting women in the guilty seat for their own oppression, and it is through this circular finger pointing that a misogynist system perseveres.

It’s one, like all other catchphrases of contemporary activism, highlighted in a soundbite liberally spread throughout the echo chambers of TikTok and Instagram. Until we have reached the intermediate ranks of feminist self-exploration, we have sparing awareness of it, yet when presented with the concept in its abstraction, it seems inherently self-explanatory.

I am angry at the patriarchy, its quirks and qualms, but I am most spiteful, even most fearful, of those shards that have entered my own heart and mind, that no amount of learning, self-discipline, self-growth, thus far, have been able to shed.

It manifests in two complex dimensions – imposing misogynistic barriers both on others and the self. It’s the latter I’m most concerned with, it being simpler to address and correct ourselves when the target is external, the phrase ‘I’m not like other girls’ becoming cemented in recent feminist theory and terminology. It is with these that we understand the male gaze we project onto others, but what about the one keeping a beady eye on ourselves?

The inner male gaze conducts a potent barometer of self-scrutinising, whether we sound too feminine or too boisterous, if we’re being too weak or too bossy, whether our male friends are taking us seriously or don’t think we’re fun enough. It instantiates other forms of internal oppression – homophobia, racism, ableism. For myself, I still seem to grimace whenever I feel sexual interest for other women. A lick of disgust appears in my head if any sapphic desire begins to show itself, causing a reflexive revolt back to a heterocentric state of mind, and it’s debilitating.

It’s evolved past simply being a male perspective, some father figure or a stealthy white-knight atop a horse who we must sexualise and serve. It’s a vast society of other women, colleagues, organisations, social systems, peers, to whom we constantly strive for acceptance, and view as conspirators in the building of a gendered battleground, when in reality they are as much subject to an oppressive society as we are.

And while we measure our distance from contemporary archetypes – the Karens, the VSCO girls, the Pick-Me girls and the Chavs – we must maintain a certain level of femininity to qualify for the validity warranted by men for women; to express masculinity, or a lack of gender ascription, receives as much revulsion as the alternative. We are walking a tightrope of spiritual entrapment, one that’s both spoiling feminine unity and denies ourselves a free identity within that population.

And finally, in all its forms, it’s a way of pinning women as the source of their misery. It is our problem that we compete, that we belittle ourselves, feel trapped in boxes and hesitate to break down the status quo. And while it is true that such phenomena have played a hand in the enforcement of gender roles, the inner male gaze is yet again the patriarchal regime nimbly extending itself to all facets of socialisation. It is both enforcing its restrictions and blaming the woman for doing so, preserving the patriarchy in innovative ways.

Maybe this is too far stretched an outcry, maybe I’m angry at myself for not yet growing into the feminist I need to be, or maybe it’s plain anger at a system that women have already been angry at for centuries. Maybe, this uncertainty towards my emotion is the very inner-voice of man in play, undermining my rationality and self-awareness.

All I know is there is a hot level of anger there, glaring at a strong sense of self-restriction I know to come from the patriarchy somehow, somewhere. When I feel defensive upon hearing other women’s successes, when I pressure myself to twist my mannerisms towards the men in the room, when I suppress any sexual desire extending to someone other than a cis-male – these are dimensions policed by a heterosexualised, Eurocentric, masculine world I’ve been taught to serve.

And so it is with this hot anger that I correct myself whenever the scales are tipped in men’s favour, as my own mind governs my own actions, and there will, with all hope intact, be a day when I am finally free. But it is not until this spiritual phenomenon lapses that we can rid ourselves completely of the gendered shackles, so drop the guilt and second-guessing – we’ve got a patriarchy to dismantle.

Alice Lang

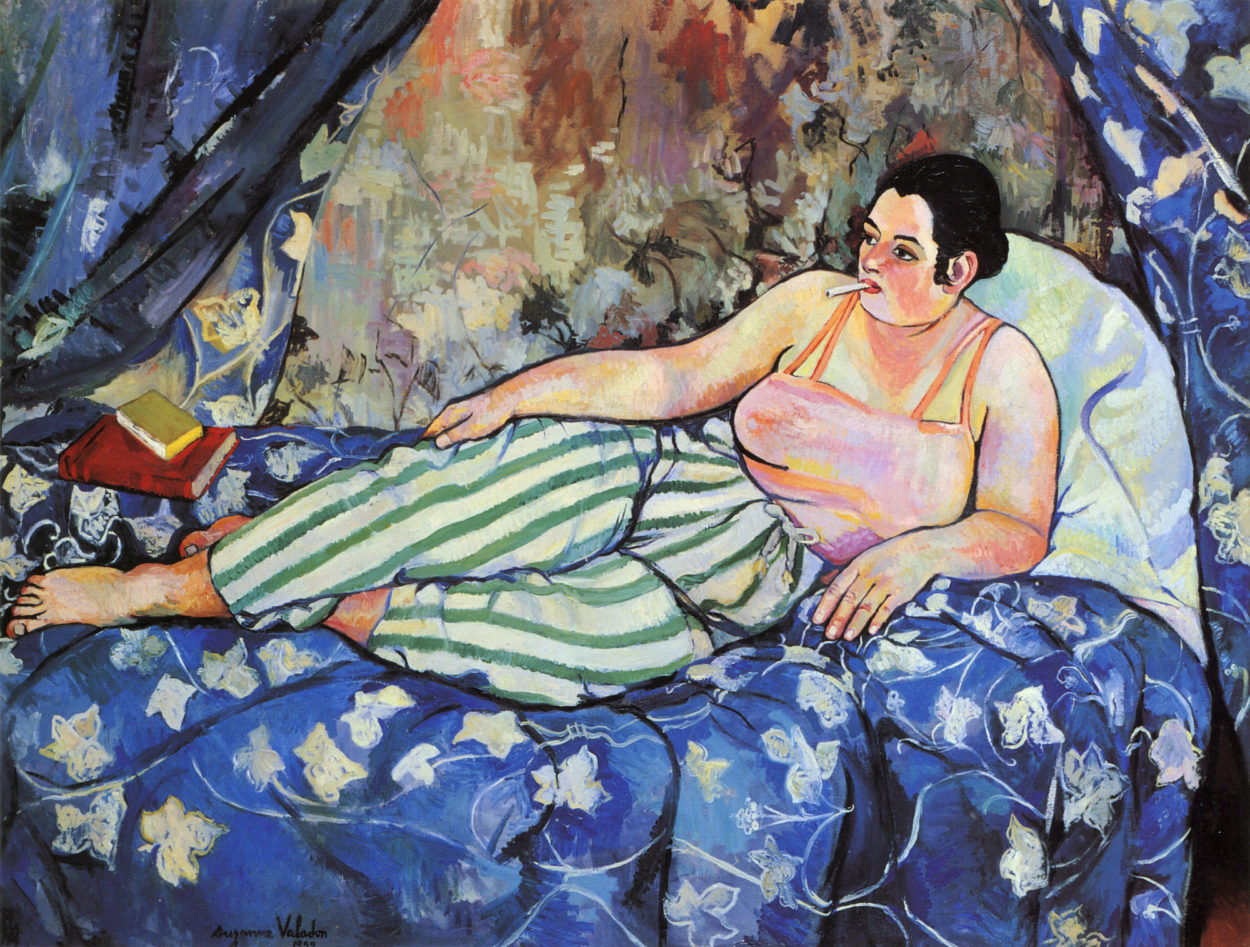

Cover image: The Blue Room by Suzanne Valadon

Leave a Comment